by Richard Condit

Carl W. Condit published Chicago School of Architecture in 1964, expanding his 1952 book entitled The Rise of the Skyscraper. It is a technological and architectural history, examining both the advancements in engineering and science as well as the artistic styles that were developed for tall, commercial buildings. It follows the stories of the prominent architects of the 1880s and 1890s -- Jenney, Burnham and Root, Holabird and Roche, Adler and Sullivan -- and then a second generation of Prarie School followers. Following the architects leads into discussions of their non-commercial and non-skyscraper forms, including houses and schools, and although the subtitle of the book gives the years 1875-1925, later architects such as Mies van der Rohe are covered for their advances in giant steel buildings.

The book helped establish the importance of the Chicago School for commercial architecture in America and thus became a tool for attempts at preserving the classic skyscrapers. Condit documents some of the preservation debates, covering in detail for example the successful program to save the Auditorium and the unsuccessful attempt for the Garrick Theater, and Bruegmann (2005) and Irish (2008) both suggest the book carried some weight in debates over which buildings to save. Although many of the important buildings downtown still stand, it is striking, for example, to note how many of Sullivan's buildings do not survive.

This led me to wonder in a quantitative way about how many of the buildings illustrating the development of the Chicago School do in fact survive in 2014. A subquestion is whether the preservationist campaign that blossomed in the 1960s helped, as documented by the rate of destruction of the early buildings prior to 1964, when Condit's book was published, and subsequently.

To carry out a rigorous assessment, I decided to use the index of the Chicago School of Architecture, specifically the entry for buildings, to create a list of Chicago buildings covered by Condit in the book. This offers an objective way of choosing buildings whose fate can be tallied. It is not a complete list of Chicago buildings, hardly, and it is not a random sample of Chicago buildings. It is a sample of buildings whose importance to the history of commercial architecture seems reasonably justified. For each building, I determined from Condit's book or from other sources when it was demolished or whether it still stands (in 2013-2014). This allows a quantitative estimate of the survival rate of buildings. Fewer buildings from earlier eras should still stand simply because there has been more time and thus more opportunity to destroy them; I examined this rigorously by examining survivorship both as a function of time and as a function of building age. Finally, I examined the survival of buildings since 1964 to address as best as possible the question of how well preservation movements changed the rate of destruction.

Methods

Building Index

There are 992 entries under the index heading Building in The School of Architecture that refer to 271 buildings in the Chicago area that are mentioned in the text. The remaining entries refer to buildings in other parts of the world, alternative names for those 271 buildings; a few references are not in fact buildings. Decisions required to resolve individual buildings are presented in a separation section with details on the methodology. Railroad stations are under a separate heading in the index and are not included in analyses here. A full table of those 271 Chicago-area buildings is provided as Appendix 1, and can be downloaded in its entirety.

Quantifying coverage

| Text Treatment | Known (Photo) | Known (No Photo) | Unknown | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1 sentence | 1 | 38 | 3 | 42 |

| 1 sentence | 10 | 43 | 1 | 54 |

| 2 sentences to 1 paragraph | 66 | 57 | 0 | 123 |

| > 1 paragraph but < 1 page | 13 | 0 | 1 | 14 |

| 1 page | 13 | 2 | 0 | 15 |

| 2 or more pages | 22 | 1 | 0 | 23 |

| Total | 125 | 141 | 5 | 271 |

Table 1. Frequency of Chicago-area buildings by pages of text coverage and photos in Chicago School of Architecture

I readily noted while examining text descriptions that many buildings are mentioned only fleetingly, without even a passing description. To decide rigorously the attention given to buildings, I estimated coverage quantitatively by counting consecutive sentences, paragraphs and pages that included some discussion of a building. To speed the process, I only counted sentences up to five, above that rounding to whole paragraphs; and I never counted paragraphs beyond three, instead rounding longer discussions to whole pages. Further details are provided in the methods section. By this measure, the two most thoroughly covered buildings are the Auditorium (9 pages) and the Home Insurance (7 pages); the Garrick Theater, Montauk, Monadnock, Carson Pirie Scott Store, and Masonic Temple had three or more pages of coverage each. At the other extreme, 42 of the Chicago-area buildings were not even granted a sentence of information, and another appeared in no more than one sentence (Table 1).

Building selection

Identified buildings. Before proceeding, I discard from further consideration 5 buildings that cannot be located: no address (or that I can find) appears, and no web search located the building name used. I have no way of knowing whether these buildings are still standing so they offer no information about the fate of books that Condit covered. They are tallied under the column 'Unknown' in Table 1 and listed in Appendix 2. The rest of my analyses are about 266 Chicago-area buildings that are identified, and these are tallied under 'Known' in Table 1.

Primary buildings. Of the remaining known buildings, -185 were barely mentioned in the text (one sentence or less) and did not have a photo. Those buildings are not part of Condit's discussion of the Chicago School of Architecture. I call the 185 remaining buildings primary buildings of the book: those that warranted discussion. A tally of how much coverage the Chicago-area buildings receive in The Chicago School of Architecture appears in Table 1; primary buildings are all those in the column 'Known (Photo)' plus those in the 'Known (No Photo)' column that have \( \ge 2 \) sentences or more of text.

Dates of construction and demolition

To make precise tallies of how many buildings were still standing at different times, I need information about construction and demolition date. Condit's book provides the former for nearly every building mentioned, and gives demolition dates for most taken down by 1963. I needed other sources to track status since 1964, and the best is the 1999 edition of Randall and Randall. For buildings not found there, I consulted a variety of different sources, and I provide details in the accompanying Methods and References sections.

.For all the known buildings (Table 1), I have confirmed status as of 2014. But a complication arose when I started calculations on the fate of buildings at intermediate times: for some buildings known to be gone by 2014, the date of demolition is not certain. In a number of cases, Randall and Randall (1999) give a date range for demolition, sometimes spanning 1950-1990. Uncertainty can be gleaned from Appendix 1 with two demolition dates, the earliest and latest possible. Where the date is known, the two dates are identical. Of all identified buildings, 31 have uncertain demolition dates; of those are also primary buildings. The Methods section provides detailed tallies of uncertain demolition dates.

Survival

Most of my work is in biology, where I study survival of individuals within populations of living creatures. A simple survival rate is calculated for a group of organisms, often called a cohort, as \( \theta = { S \over N} \), where \( N \) is the number alive in the cohort at the start, \( S \) the number surviving some time later, and \( \theta \) is the symbol for survival rate. Mortality rate is defined as \( \mu = 1 - \theta \).

A common example is where the cohort of \( N \) individuals is a group of young, all born at about the same time, and \( S_t \) is the number still alive at any time \( t \) later, meaning that \( t \) is also the age of the organisms. Applied to Chicago-area buildings, I work with cohorts of similar age by grouping buildings by decade of construction: all those built in the 1880s, for example. It is not, however, necessary that a cohort all have the same age, indeed a mixed cohort might be organisms of any age alive at a certain time. It is possible, for example, to calculate \( { S \over N} \) of all primary buildings covered by Condit at one point in time, such as the year 2014. Slightly more complicated is to start with a mixed cohort and tally those that survived to a fixed age, such as 50 years. Then the count of survivors \( S \) is not made on a fixed date, but on a different date for each building.

Survivorship curves

Survivorship is defined as the number of survivors \( S_t \) out of \( N \) individuals as a function of time \( t \), and is thus simply a series of survival calculations through time. The survivorship graph starts at \( N \) when \( t=0 \) and is monotonically non-increasing: it can only go down or remain level. Ordinarily, survivorship is expressed as a fraction, \( \rho = { S \over N} \), so the initial value is \( \rho=1 \). Applied to buildings, I take a cohort of size \( N \) and find \( S \) every decade (not every year, since few buildings are demolished in any one year).

Uncertain demolition and survival

Calculations of survival are complicated by cases where there is uncertainty about dates of demolition. One plausible approach to get around this would be to eliminate from all survival calculations those buildings with uncertainty, but this creates a sizeable bias: excluding buildings known to be demolished as of 2014 inflates the survival. A better approach is to exclude those cases only where necessary. For example, if a building was built in 1900 and demolished between 1950 and 1990, then it can be included in survival calculations up to 1950, then again after 1990, but has to be excluded for all estimates in between. This does not create an obvious bias, because in any year during 1950-1990, it may or may not have been standing. The Methods section describes more thoroughly how calculations were done to avoid uncertainty.

Results

Proportion of surviving buildings

Of the 185 Chicago-area buildings treated in some depth in the The Chicago School of Architecture, 83 are still extant in the year 2014 and 102 have been demolished, an overall survival of 44.9%. When Condit completed the book in 1964, 121 were certainly still standing; 39 have been taken down since 1964. The survival rate as of 1964 was thus 0.654 or 65.4%, and the rate from 1964 to 2014 was 0.686 or 68.6%.

Survivorship and age

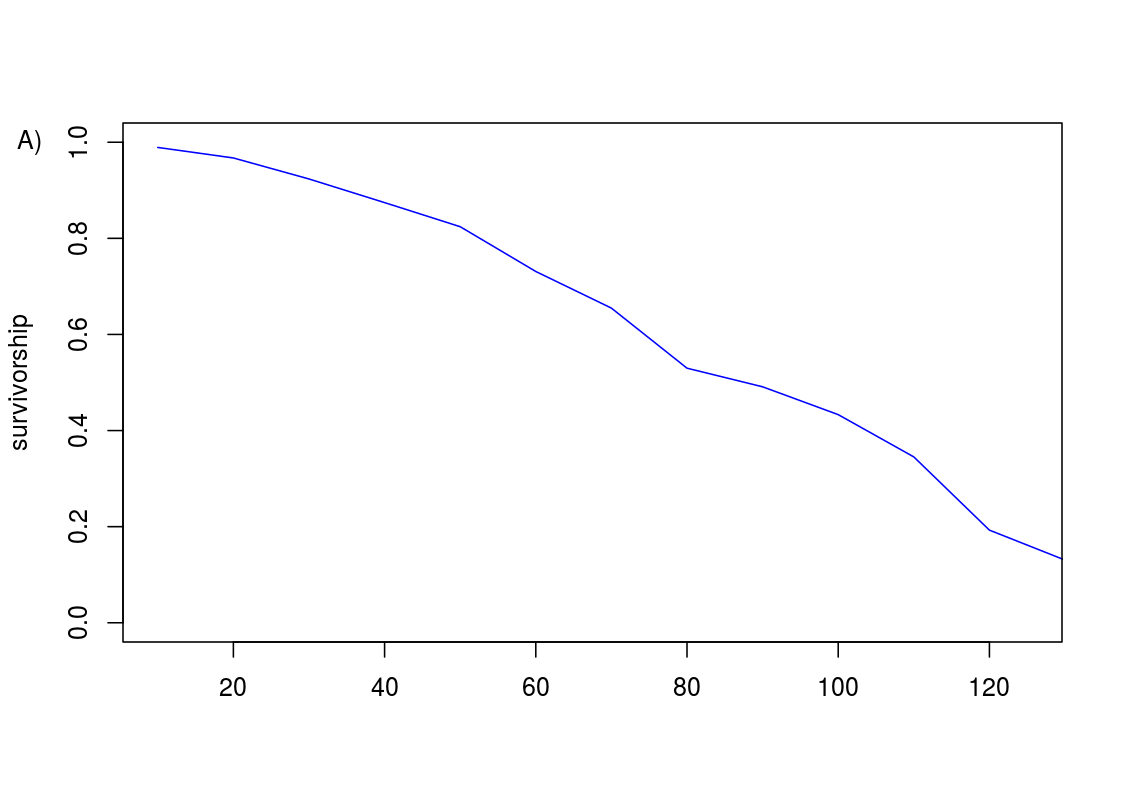

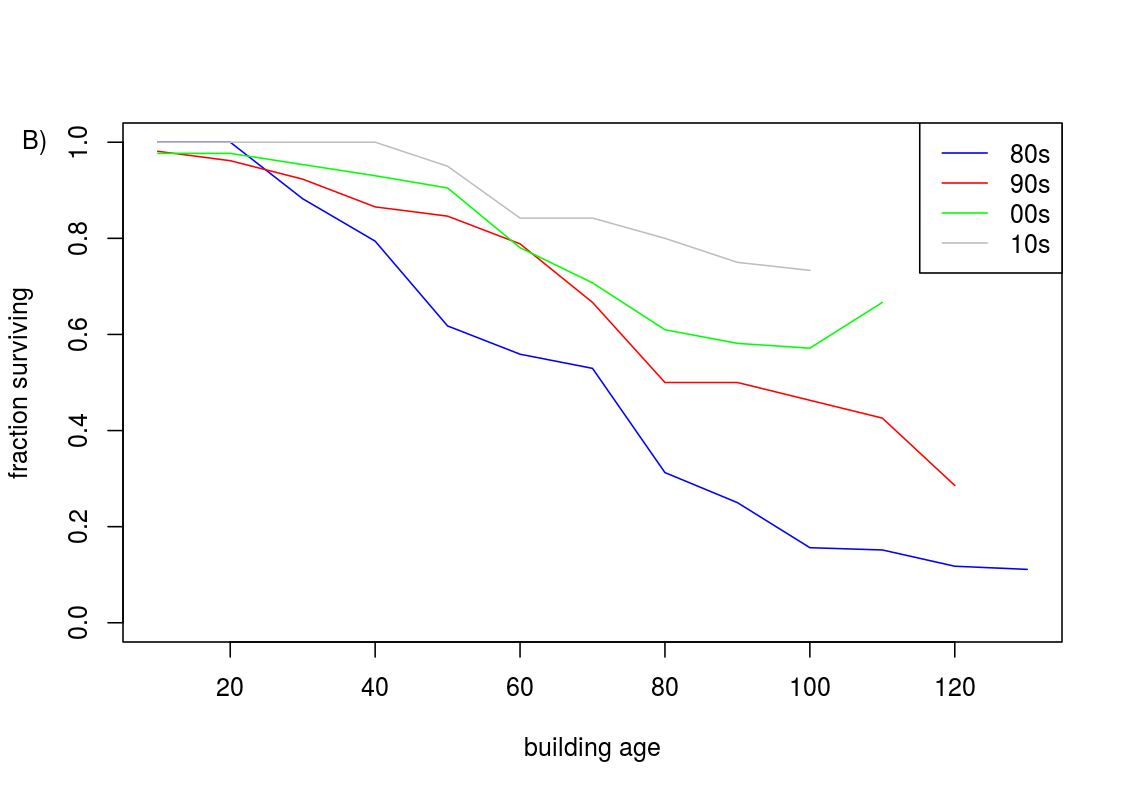

Figure 1 shows survivorship of all 185 primary Chicago-area buildings as a function of building age. Half the buildings survived 90 years, and 20% to 120 years (Fig. 1).

Figure 1A. Survivorship as a function of age for the 185 primary buildings treated in The Chicago School of Architecture. The vertical axis gives the number that survived each 10 year window as a fraction of the total that were extant at the start of the 10 years, excluding any whose demolition was uncertain during that window (as explained in the section Survivorship curves under Methods). The horizontal axis is building age, so a building built in 1883 is counted as still standing at age 60 if it survived until 1943.

Figure 1B. The fraction of buildings at the start of a 10-year window that were destroyed by the end. This is based on the same samples as the survivorship tally in the top panel, corrected for uncertainty in the same way.

Older buildings were more likely to be destroyed, as shown by the steady increase in demolition risk with age over 80 years (Fig. 1, bottom). Buildings seldom were taken down in their first 20 years: two of the 185 buildings were taken down in their first decade, and four of the 185 survivors came down in their second decade; both risks well below 5% per decade. Subsequently, the risk rose to 10% by age 70, then abruptly to 20% at age 70-80 (Fig. 1, bottom). After age 90, however, the survival rate went down to a moderate 5-10% per decade.

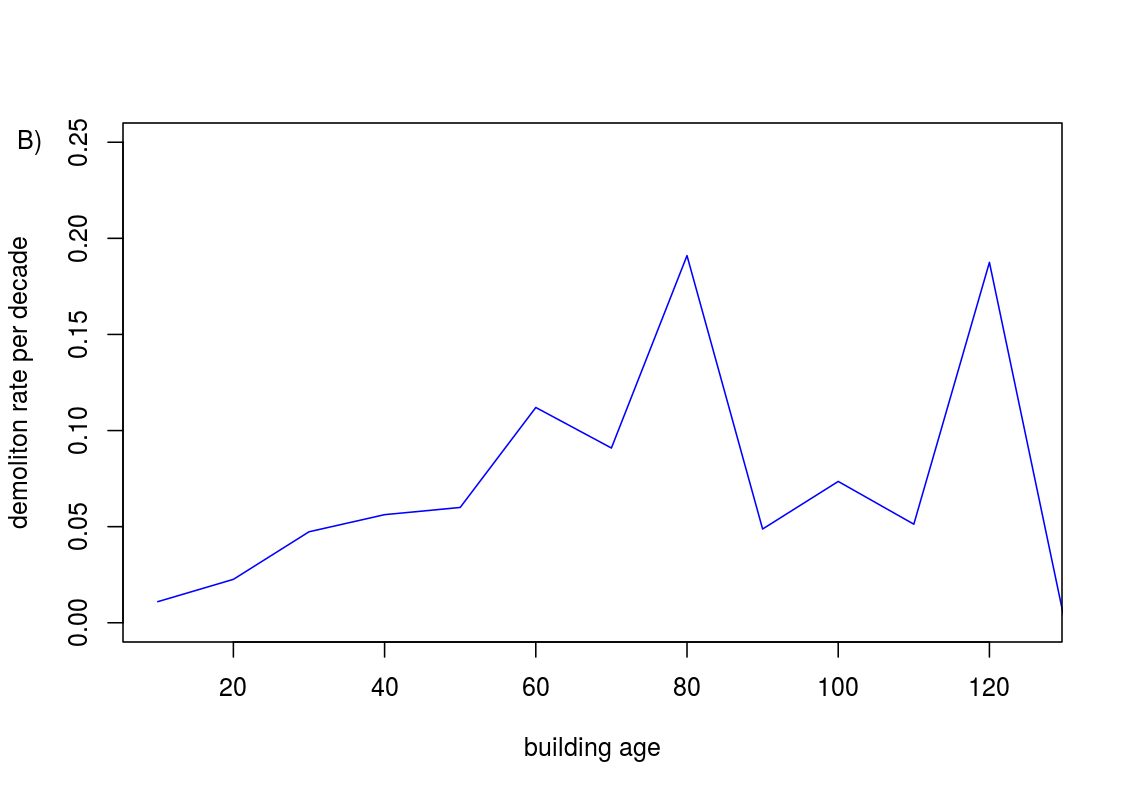

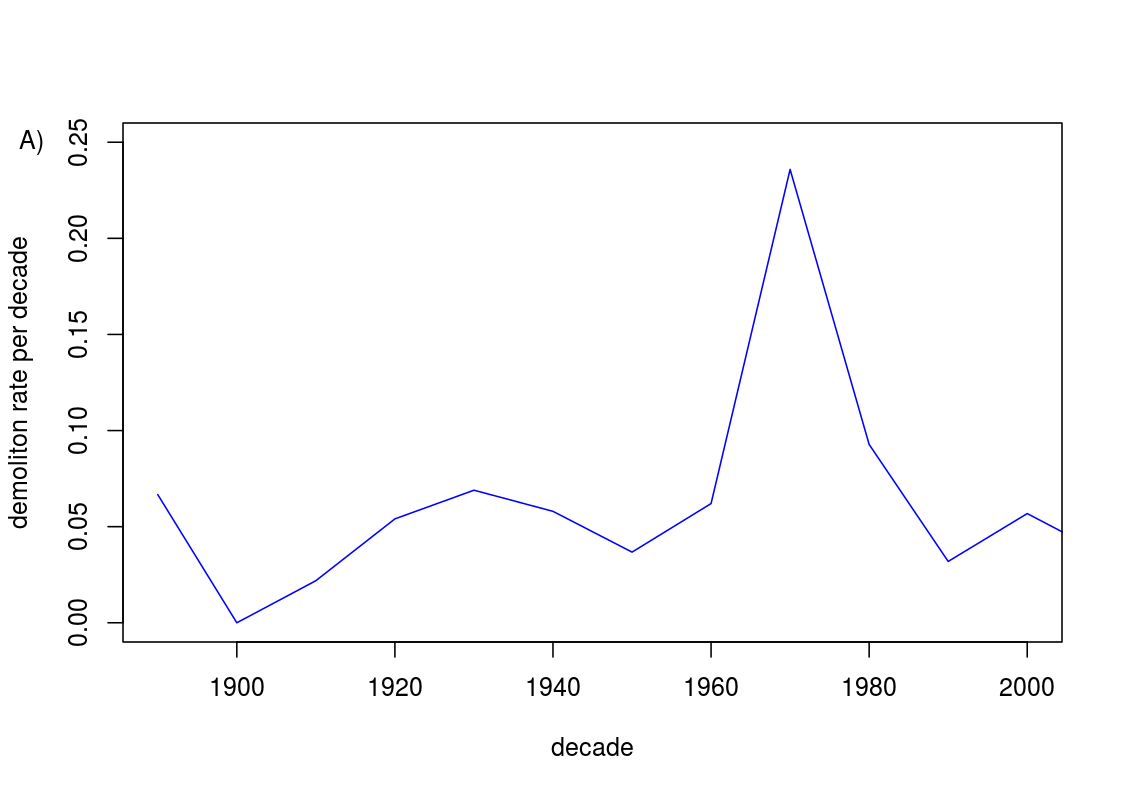

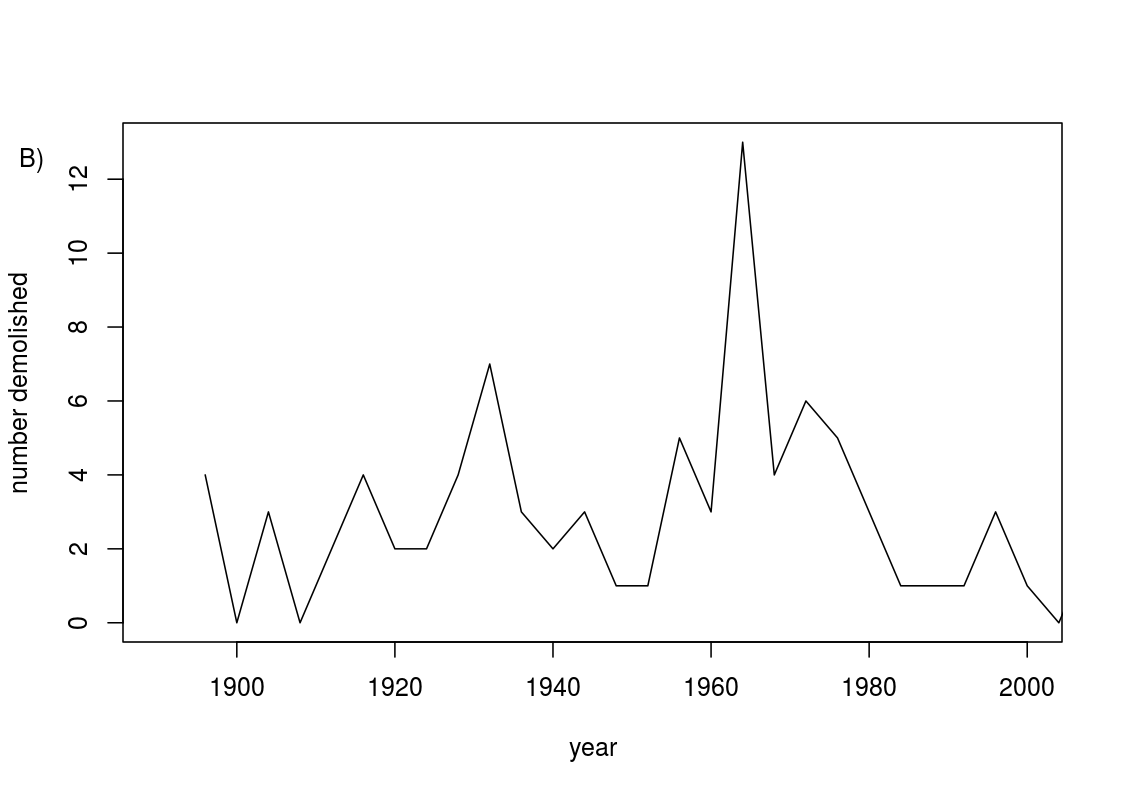

Figure 2A. Demolition risk per decade, calculated from samples of buildings extant at the start of each decade and whose fate by the end of the decade was certain. Each value appears above the last year of a decade, that is the peak appearing at 1970 means the risk during 1960-1970.

Figure 2B. Bottom: Number demolished per four-year interval. Data are the same as in top panel, but with narrower intervals to show peak times more precisely, and given as numbers, not rates.

Survivorship through time

The risk of demolition per decade shows that the greatest rate was during the 1960s (Fig. 2, top). The elevated demolition risk buildings encountered at 70-80 years of age (see Fig. 1) comes from the 1960s peak: for many buildings completed in the 1890s, age 70 was reached during the 1960s. A more refined graph of destruction period (Fig. 2, bottom) shows that the biggest peak happened just before Condit published, during 1960-1964, when 12 of the buildings were taken down. Those include the Garrick Theater, the Great Northern Theater, the Hyde Park Hotel, and one from before the 1871 fire, the Lind Block. A smaller peak of destruction happened in the early 1930s (Fig. 2, bottom).

Survival by construction era

Whether a building has survived to the present depends considerably on when it was built. Nearly all buildings treated in the The Chicago School of Architecture that were completed prior to 1890 have been demolished (35 of 41, or 14.6% survival). Survival for buildings built during the 1890s is 40%, and even higher for later buildings (Table 2).

| era | demolished | extant | survival |

|---|---|---|---|

| early | 13 | 2 | 0.133 |

| 80s | 28 | 4 | 0.125 |

| 90s | 33 | 22 | 0.4 |

| 00s | 18 | 23 | 0.561 |

| 10s | 4 | 14 | 0.778 |

| late | 3 | 17 | 0.85 |

Table 2. Survivorship to the present (2014) of buildings treated in The Chicago School of Architecture by construction period. Early includes all buildings completed prior to 1880 and late all after 1920.

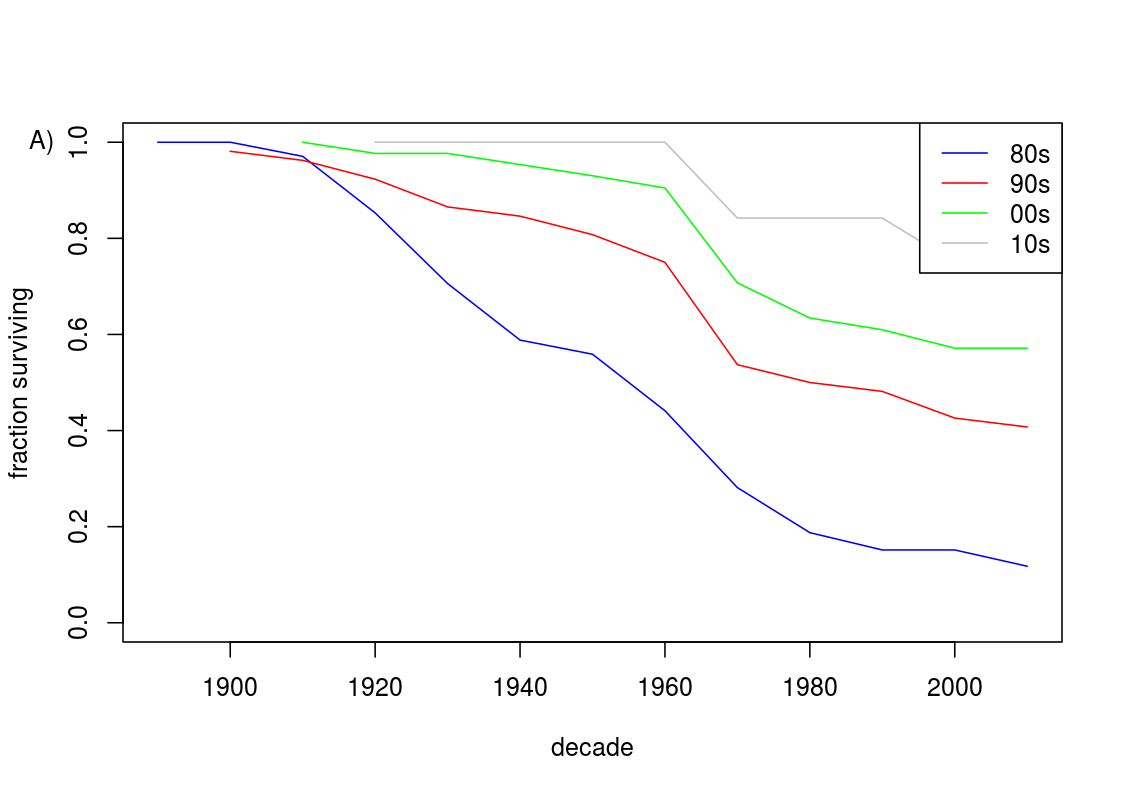

The poor fate of the 1880s group of buildings cannot be attributed simply to their greater age. When aligning the survivorship of buildings from different eras by the buildings' ages, it is evident that the early buildings were at greater risk through most of their existence (Fig. 3, bottom). For example, just 59% of 1880s buildings survived until age 50, whereas 87% of 1890s buildings did. The four decadal cohorts can be compared out to 90 years of age, when survivorship was only 25% for 1880s buildings but 75% for those from the 1910s (comparing blue and gray curves in Fig. 3, bottom).

Figure 3A. Survivorship curves of buildings from The Chicago School of Architecture grouped by decade of construction, aligned by calendar year, so curves for successive groups start 10 years apart.

Figure 3B. Survivorship curves of buildings from The Chicago School of Architecture grouped by decade of construction, aligned by building age, so all curves begin together, at age zero. This alignment shows clearly that buildings from the 1880s fared worse than later buildings, even at the same age. In both curves, buildings are omitted from any survivorship calculation where there was uncertainty about demolition at the specified time. That omission is what makes it possible for the curves to rise.

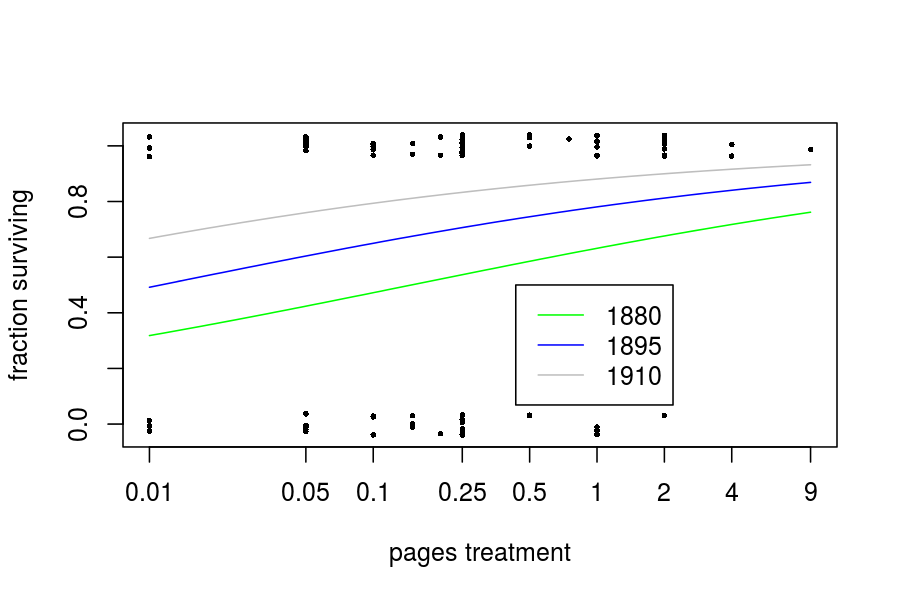

Survival and treatement in the text

Total survivorship from construction until 1964 was 50-60% for all buildings treated with two sentences or more in The Chicago School of Architecture. There was no clear trend between survival and treatment (Table 3), suggesting Condit was equally likely to write a lot about buildings that had already been taken down as he was those still standing. Subsequent to 1964, there was a relationship between treatment and survival: 11 of the 12 most heavily covered buildings survived, but much lower fractions of buildings to which he devoted less text (Table 3).

| Treatment | Buildings | Demolished | Standing | Demolished | Standing | % Survival | % Survival |

| < 1964 | 1964 | 1964-2014 | 2014 | < 1964 | 1964-2014 | ||

| < 1 sentence | 17 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 35.3 | 50.0 |

| 1 sentence | 31 | 13 | 18 | 7 | 11 | 58.1 | 61.1 |

| 2 sentences to 1 paragraph | 88 | 35 | 53 | 24 | 29 | 60.2 | 54.7 |

| > 1 paragraph but < 1 page | 14 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 50.0 | 71.4 |

| 1 page | 13 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 61.5 | 50.0 |

| 2 or more pages | 23 | 11 | 12 | 1 | 11 | 52.2 | 91.7 |

| Total | 186 | 82 | 104 | 41 | 63 | 55.9 | 60.6 |

The relationship between text treatment and survival since 1964 is supported most clearly when construction date is also taken into account (Fig. 4). The multiple regression demonstrates that when holding age constant, there remains a substantial treatment effect: buildings covered more thoroughly in the 1964 book were more likely to survive from 1964 to 2014 than those covered little. That the gray curve is above the green then blue curves shows the strong effect of building age on survival, even after 1964 (as Fig. 3 illustrates).

Figure 4. Survival rate from 1964-2014 as a function of the number of pages of treatment devoted to an individual building in The Chicago School of Architecture. The model was a multiple logistic regression of survival against the logarithm of pages plus the year a building was built. The graph shows survival against treatment, each curve with construction date fixed at a constant age.

Discussion

When Carl Condit published his 1964 book, The Chicago School of Architecture, 34% of the books he chose to write about had been destroyed. He was of course aware of this in making the selection of buildings to include. A surprising result is the peak in destruction right around publication: 12 of the buildings he covered were destroyed in 1960-1964. He noticed and commented on some of those, such as the Garrick Theater, a building to which he devoted five pages. Indeed, Irish (2008) already noticed this, calling attention to the many buildings desribed in the 1952 edition that were demolished by the 1964 edition.

Demolition of the buildings he wrote about subsequently was outside his control, except to any extent that his efforts influenced the preservation movement, as Bruegmann (2005) and Irish (2008) argue. Disappointingly, since 1964, another 20% of the buidings he wrote about were destroyed (39 were demolished since 1964). Now fewer than half of the 185 primary buildings he wrote about remain.

A glimpse of optimism is the success of the preservation movement. There is a group of 12 buildings to which Condit devoted his most attention, and nearly all of these are now secure. Those 11 remaining, the Auditorium, Carson Pirie Scott Store, Congress Hotel, Charles Hull House, second Leiter Building, Manhattan, Marquette, Monadnack, Old Colony, Reliance, and Rookery, are established Chicago landmarks very unlikely to be demolished any time soon. Of the buildings standing in 1964 that Condit wrote at least 2 pages about, only the Stock Exchange is gone, taken down in 1972 amidst considerable controversy. The Hull House group was slated for destruction as Condit wrote the book, and he devoted a long discussion to the fight over its protection. Indeed, one of the 10 buildings was finally preserved and remains on the campus of the University of Illinois.

Hidden within the summary statistics about the fate of Chicago School buildings is the sharp difference between those built in the earliest phase, in the 1880s, with later buildings. Nearly all of the 1880s buildings covered by Condit are now gone: of commercial buildings, only the Auditorium, the Rookery, and the Jeweler's remain. (The Glessner House also counts, as it has a photo in Condit's book and was built in 1886.) Many of these early buildings were gone by 1964, but several more since. Most recently, Sullivan's Wirt-Dexter building was destroyed by a fire in 2006, after it was protected with landmark status.

Buildings completed in the 1890s and the 1900s were also important in Condit's treatment, and many more of these buildings have survived. Better survival of buildings finished since 1890, compared to pre-1890 buildings, is clearly not simply a matter of age, as demonstrated by aligning the different groups by construction date (Fig. 3). Other explanations must be sought: perhaps construction methods advanced a great deal from the 1880s to 1890s, making it easier to restore the later buildings to maintain their usefulness.

In sum, fewer than half of the 185 buildings that formed the basis for Condit's presentation on the Chicago School are still standing. But there are still 82 that can be visited, and it seems likely most of these will remain for the next few decades. Many of these are well-known loop buildings considered illustrations of early skyscrapers, both cage and steel-frame, described in remarkable detail by Leslie (2013). Others described by Condit, though, are spread about less-known and seldom visited Chicago-area neighborhoods, and not all are skyscrapers or even commercial: there are several schools and private homes. I encourage a look at Appendix 1 to find buildings that Condit covered and are still standing, then check what he wrote to see how it holds up.

Appendices

Appendix 1. A complete table of 271 Chicago-area buildings appearing The Chicago School of Architecture to view or download.

Appendix 2. Table of unidentified Chicago-area buildings from The Chicago School of Architecture to view or download.